Opportunity of a Lifetime: A Big Cross Country, DRCO, and other stuff

Prologue

Solly (the airplane broker at our local airport) and I were chatting in the terminal one day, between flights on a solid VFR day, when the conversation turned to buying, selling, and delivering airplanes. Suddenly he said: "You know, there is an airplane in Regina that needs to go to St. Johnís Newfoundland. Itís a Cherokee 140. Are you interested in taking it?" It took less than a millisecond for my decision: "Sure! Iíd love to!" ... And thatís where it all started.

Preparation

I started the flight planning the next day. Solly had told me that the aircraft was having some work done in Regina before it would be ready, so I probably had a week to clean up some business things, and get ready to go. I spoke to Solly quite a few times over the next few days, for status reports of the planeís readiness, and other details that I might need to know.

My flight planning software told me that the trip would encompass over 2100 nautical miles, almost twice as far as any other trip that Iíve done. (Florida/Bahamas is about 1100 nm.) It also told me, in a roundabout way, that there are very few airports in Northern Ontario in a direct line from Regina to St. Johnís. (I have it preprogrammed to select airports every 250 nm, but a few hops were no less than 400 nm ... something that a Cherokee should not be asked to do!) So I had to "finesse" the AutoRoute function a little bit, by selecting some airports that were farther south, in a more populated area. This resulted in the flight plan growing to almost 2200 nm.

OK, quick math. I usually use 100kts as the airspeed, and 10 gph as the consumption for Cherokees. This equates to 5 hours on 50 gallons, covering 500 nm, if the tanks are used to exhaustion. Of course, VFR fuel requirements are "... to the place of intended landing and thereafter ...for 45 minutes at normal cruising speed (RAC 3.13.1[a])", so it really means 4:15 hours and 425 nm. Now, I add my own margin of safety to this, which realistically means 3:00 hours and 300nm. This extra margin allows for bad winds, traffic vectors, taxi and wait time, and possibly busy circuits at the destination. Thatís why I like to have the software automatically select 250nm legs. I still play with it sometimes to increase the legs to 300 nm for really long trips. And this was going to be one of those!

So whatís 2200 nm divided by 300 nm legs? Itís at least 8 hops, if every leg covers as much as possible. But, there were other factors to consider as well. I had to stop in Halifax, since the new owner might decide to take possession there instead of St. Johnís. And, I wanted to stop in Montreal to visit my nephew. With these additional constraints, the whole journey was now likely to be 10 stops. And, since the aircraft and I are both "VFR only", even those 10 stops were only considered "working targets".

With the flight planning well under way, I still had to find a way to get to Regina. That too, was no easy task, since I knew that Iíd be given the go-ahead as soon as the plane was ready, and that wouldnít leave me any "7-day advance booking" time for the airlines. But that too, was overcome.

With no more obstacles, and the plane ready, the call finally came from Solly: "Dav1d, the plane is ready to you to fly it. Are you ready to go?" I got the necessary paperwork from him, gave him a copy of my proposed routing, and departed the next day for the adventure.

Day Zero (Tuesday) ... The Outbound Journey

The trip to Regina included a flight on a Canadian Airlines B737 to Winnipeg, with a 3-hour wait for the next leg on a Canadian Regional Dash-8 to Regina. On the B737, I asked for permission to visit the flight deck, and managed to stay for the entire rest of the flight, including the landing at CYWG. It was a smooth landing, flown by hand, because this B737, like most, had no autoland capability.

So, what can a pilot do for 3 hours in a strange airport? Visit the control tower, of course!

It took a few minutes to locate the tower, and get the necessary permissions, but after that, it was all easy. I spent 2 hours in the tower, talking to the controllers, and watching how they operate the systems.

Winnipeg Tower is a big place. Thereís enough room for 7 active staff, and a central console for the manager, but, at this time, there were only 4 active staff, including a manager. The active positions were: ground, tower, and assistant. One of the assistantís jobs is to get the strips that are printed by Winnipeg Center into the holders and distributed to the appropriate controllers.

The assistant, Lionel, took time during his slow moments to show me the systems and explain the computers. I spent time looking over the shoulders of the ground and air controllers.

One of the most interesting things was the handoff from one controller to another. When a new controller is coming to relieve an active controller, there is a short length of time when the new controller just stands and watches the active controller, to get familiar with the traffic being controlled. While heís standing there, the active controller is not only talking to the airplanes, but heís also explaining the targets to the replacement. This particular handoff only took about 3 minutes, but I can imagine how much more complicated it could have been had more airplanes been involved.

As is typical for busy airports, they have ground radar as well as airborne radar. The ground radar is powerful enough to pick out the ground handlers and paint them on the screen! (Unfortunately, the radar is so powerful that it is located on the roof of the control tower, behind a lead shield. Access is strictly forbidden while it is operational, as it would fry a human in seconds!)

Looking out across the field, we could see the building that houses Winnipeg Center. It was too far to walk, and I had no car, so I passed on visiting the center. (Maybe next time?)

I thanked all the controllers for the visit, and told them that Iíd be flying into their airport the next day in a VFR Cherokee. They said theyíd watch for me.

The second leg of the journey, a Dash8 from CYWG to CYQR was uneventful.

|

|

|

When I landed at CYQR, I decided to find the Cherokee as soon as possible. I figured that once I got everything that I needed, I could go to the hotel, and get a good nightís sleep, so I could start out early in the morning. I had been told that the Cherokee was at the Shell AeroCenter, so I went straight there.

C-GCRZ was waiting for me. It was a blue and white Cherokee 140B, probably 1969 vintage. I walked right up to it, and looked inside. Then I set out to find my contact person. After some searching, and asking the line crew, I finally found Richard. He had just flown the plane in from Estevan (about 1.2 flight time). I mentally decided that this was a good thing. He and his father had just done a 100 hour inspection, and the check ride made me feel more comfortable. Of course, I was still going to do a very complete inspection, but knowing that it had already flown meant that most of the airworthiness was already proven.

Richard introduced me to CRZ. Very nice interior (baby blue), nice exterior, almost no rust, even underneath the back seats. Avionics were sparse: one flip-flop comm (with no nav at all), one ADF, one mode C transponder, and a Flybuddy LORAN. The standard 6-pack of instruments was all there, and apparently functional. An EGT gauge, and a CHT gauge were installed as well. On the down side, the clock was dead, and there was no VOR at all. In short, a nice airplane, but not many toys inside. (I had expected this, so I had brought my GPS with me.)

Richard and I went through the journey log and the technical logs, and he gave me some additional pointers on the aircraft ("... the CHT on number 3 shows 180° , I would have preferred 160° ..."), and then he drove me to the hotel.

I didnít see much of the city, except for a sign that said "Welcome to Regina, home of Sandra Schmirlerís Olympic Curling Team!".

I took the technical logs, the journey log, and the revised weight and balance sheets to dinner with me, and skimmed them briefly, hoping Iíd have enough energy left to read them in bed before falling asleep. No such luck.

Day One (Wednesday) ... CYQR-CYWG-CYQT

I got up early in the morning, ready to begin the real adventure. I called FSS, and they explained that the weather was CAVOK all the way to Winnipeg, and beyond that all the way to Thunder Bay. Thatís exactly what I had flight planned, and it looked like it was going to work out! I was ready to go within half an hour.

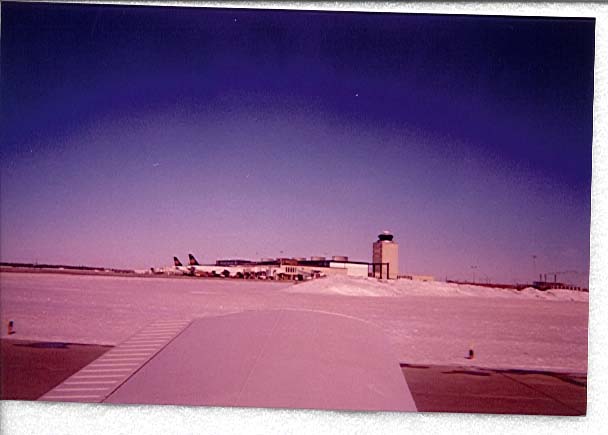

I had a good nightís sleep. The plane didnít. I had been asked if I wanted to hangar the airplane the previous night, but I declined. Now, I knew why they had asked. The temperature now (at 0900 local) was -20° C, with a wind chill of -24° C, and CRZ was covered with frost, stem to stern. I tried to scrape some of it away, but quickly found out how tedious and long a task that might turn out to be. I spoke to the line crew, and we discussed a few options. Either I could put it in the hanger now, for a few hours, or I could have it de-iced. The thought of losing a few hours in the beautiful VFR prairie sky, and falling behind schedule outweighed the hangar option.

I sat inside the airplane while they de-iced the exterior by flushing it with glycol. I used this time to get the ATIS, prepare my charts, and get setup for flight. Once the de-ice was done, and they had backed away, I tried to start the engine. No good. The engine was far too cold to start. I needed a "pre-heat" as well. I decided right there that I should carefully consider my options for the next night, including calling FSS for the overnight weather. But that was still hours and miles away. First things first. They used a large heater with a fan, which they called a "Herman heater". After about 20 minutes, the engine compartment was nice and warm.

I departed CYQR around 1700Z (1100 local). The plane flew like its true Piper heritage. Smooth, clean, responsive. Of course, with just me and my personal things on board, it was light. I punched in the direct course to CYWG in the onboard Flybuddy LORAN, as well as my Garmin GPS, and made sure they agreed (within reasonable limits). Then, I relaxed for the long flight.

The prairies are ... flat.

|

|

|

Suddenly (which really means more than three hours later!), I was approaching Winnipeg. I tuned in the Winnipeg ATIS, and called Winnipeg Center from 35 miles out, and had them bring me right in. I had tried to use flight following directly out of Regina, but there is limited radar coverage in some areas. So Winnipegís voice was much appreciated. An uneventful landing ended the first leg of the first day of my long adventure. As I taxied to the Shell AeroCenter, I thanked the controllers that I had met the day before in their tower, and told them that Iím in for fuel only, and would be out again shortly. They wished me luck on the rest of the trip.

I knew the trip to Thunder Bay would be a long one. But I had calculated that I could get there just around sunset. I checked the lights on CRZ (remembering that Richard had said that they checked out okay.) I also checked with FSS for the official sunset time, and the CFS for hours of operation at CYQT (both the tower and the FBO). Iím night rated, and the lighting systems checked out okay, so I had no hesitation in taking off. I phoned the FBO anyways, just to make sure that someone would actually be there. Then, I departed Winnipeg International Airport.

Suddenly (see earlier definition of this word), I was approaching Thunder Bay. It was about 15 minutes past sunset when I spotted the lit runway. Of course, the tower controller and I had been chatting about it for the last ten minutes. Since he was the only one in the tower, I stayed on the air frequency for progressive taxi instructions right up to the Shell AeroCenter.

I was greeted by the line crew, and asked how long I would be staying. I said "Overnight", and quickly asked "Do you have any indoor hangar space for tonight?" The short answer was no. The longer answer was "We could find out if Bearskin can let you use their hangar, but itís going to cost you big bucks." I told him that I would check with FSS and then decide if we should try for an indoor spot. FSS said that it would be a cold night, and that frost was likely. I decided that I would chance the weather, and use the cheaper "Herman heater" in the morning. If necessary, I could redirect some of its heat onto the wings. I packed up the airplane for the day, and called the hotel for the shuttle pickup.

My day ended at the Airlane Hotel in Thunder Bay. As soon as I got to the room, I called Solly to report on my status. Then I turned on the TV and settled in, but when I realized that I had no idea what was happening on the screen, I turned it off. My brain went off too.

Day Two (Thursday) ... CYQT-CYXL-CYYB- CYUL

I woke up eager to get going. Before even opening my eyes, my fingers were dialing Flight Services. Yes! Another fabulous day. It took less than an hour to pack, check out, and get to the airport. Thatís when I discovered that Thunder Bay can be as cold as Regina. Another -20°C day!

|

|

|

Of course, the airplane had some frost on it, as I had suspected, but not nearly as much as on the first morning at Regina. I talked to the line crew about the preheater, and they got it setup within minutes. While it pumped hot air directly underneath the cowling, I used a large broom to sweep off as much of the frost from the control surfaces as I could. I stopped every few minutes to stand in front of the preheater and warm myself up too. I even took one of the hoses from the preheater and "sprayed" warm air over the wings to help melt the last thin layer.

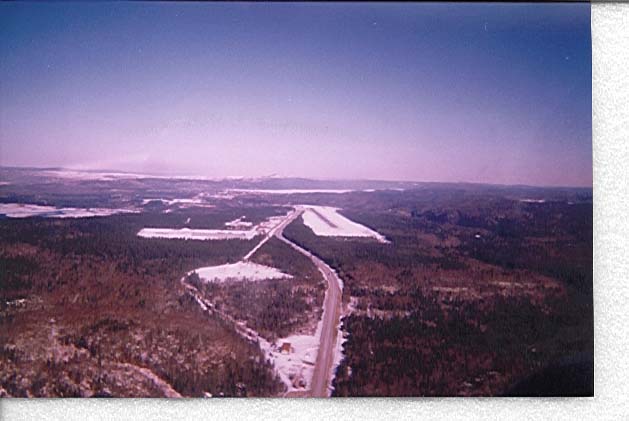

I was ready to go by 0900 local. The flight planning called for 3 stops today, so I wanted to get going as soon as possible. I originally planned to fly from Thunder Bay directly to Sault Saint Marie, diagonally across Lake Superior, and I had brought a life vest with me for the trip. But when I called FSS to file, they suggested that the life vest was useless in Lake Superior, and I might want to consider following the north shore of the lake. I agreed, and modified my flight plan to include a fuel stop at Wawa (CYXL) instead of going as far south as the "Soo" (CYAM).

I called flight services for the usual weather briefing, and asked about flight following (which is continuous radar coverage much like an IFR environment). The specialist told me that there are large areas with no radar, but I could always reach flight services on 126.7, via "DRCO" outlets. I have never used a DRCO, so I asked what that meant. He explained that Dialup Remote Communication Outlets donít have a continuous link to a flight service station. Instead, they have a telephone that dials the FSS. You have to click the mike 4 times on 126.7, and wait, listen to the dial tone, listen to the digits being dialed, listen to a mechanical voice saying "Link Established", and then call "Thunder Bay Radio" (or whatever). I made a mental note to try it enroute.

|

|

|

The trip to Wawa, around the north edge of Lake Superior was beautiful. I turned Wawa around in under 30 minutes, and got airborne again. North Bay was only 240 miles away, so it would be a quick hop (compared to some of the others).

North Bay was also a quick stop. I was anxious to get to Montreal.

By the time I got to Montreal, it was just sunset. I have flown into Montreal many times, so I am familiar with the zone. Although this time it looked different. I was approaching from the northwest, instead of the usual southwest, so it took a little bit longer to find the runway. Of course, I had been talking to Montreal Center since approaching the Ottawa zone, so he reeled me in all the way, like a marionette. I pulled up to my favourite FBO (Shell AeroCenter), and told them that Iíd be staying for the night. I called FSS to determine if I should hangar the plane, and they explained that there was only a slight chance of frost. I decided that I was making good headway, surfing the high pressure ridge from the prairies all the way to the maritimes, and that I deserved a late start the next morning. The plane could warm up in the sunlight of the morning instead of paying big bucks for the overnight spot indoors.

I called Solly on my cell phone during the cab ride to my nephewís place. He told me that the plane should be delivered to Halifax, instead of St. Johnís. I was disappointed that I wouldnít be taking it right to the east coast.

My nephew and I had lots of catching up to do, so we talked until late into the night before exhaustion got the better of me. I was glad that I had already decided to sleep in the next morning. The next dayís flight would take me into the Maritimes, where Iíve never flown before, so I wanted to be sure that I was in good shape to handle it.

Dreaming about the last two daysí flying was a good way to end the day.

Day Three (Friday) ... CYUL-CYFC-CYHZ

The morning sunshine in Montreal was magnificent. The high pressure ridge was still with me, and the temperatures were co-operating as well. I got airborne by noon, the latest starting time of the whole trip. I used flight following until well out of the control zone, before radar service was terminated, and I was told to squawk 1200.

The direct flight from Montreal to Fredricton took me over Maine, but since I wasnít going to land, I didnít have to call or clear with US Customs. I did, however, need to use a DRCO to get the weather report for Fredricton. Click, click, click, click, dialtone, digits, "Link Established", and then the radio call. No problem.

Fredricton was quick. While the plane was being filled, I called Solly again. It was 1530 local (I was now in the third different time zone for this trip!), and I wanted to get the plane to Halifax before the weekend. So I needed to make sure that Solly had setup someone to meet me and take possesion of C-GCRZ. I couldnít reach him, but I left a message with Paula, his assistant, that I would be in Halifax in under 2 hours. I also tried to reach the original contact person, in St. Johnís, but he too was out of his office. I decided to make the trip anyways, and keep the keys until someone could meet me the next morning.

This call to FSS was the first one that I didnít like. They reported low (2000í) ceilings over most of Nova Scotia, but below the clouds there was 15 miles visibility. I was also told that the clouds over the Bay of Fundy can drop low, and to be extra cautious. When asked about survival gear, I again told them about the life vest, and again was told how little use it would be in the waters of the Bay of Fundy. Regulations say that I must carry it, but common sense says that I wouldnít last more than a few minutes in the icy waters of the Atlantic Ocean.

I thanked the specialist for the information, and departed southbound for Halifax. Fredricton is situated immediately north of a live missile testing range, so the departure procedure on the southbound runway calls for an immediate left turn after takeoff. Similar to "noise abatement procedures", only more deadly if you disobey the instructions. I complied fully. After I had gotten around the restricted area, I said goodbye to the Fredricton tower, and proceeded on my way.

Thatís when I started seeing the clouds.

Most of the Maritime provinces that I flew over are very near sea level, so when they say ceilings of 2000í, they mean both ASL and AGL. That saved me from having to calculate the difference. I filed my flight plan for 2000 the whole way, but actually snuck it down to 1500í crossing the Bay of Fundy. As reported, the visibility below the clouds was excellent, but in the clouds... it wasnít so good. When I saw the north shore of Nova Scotia, I figured that the hard part was over, and I was home free. But thatís not what Halifax Tower told me.

I was 20 miles out, just entering the second ring of their control zone, when the tower controller said that a snow squall at the airport had dropped visibility to less than half a mile. He asked me if I could come in IFR, but that conditions were almost below IFR minimums. I told him that the aircraft did not have the required avionics to land IFR, and I was not IFR certified. I looked around and estimated that I still l had 15 miles in all directions. The controller said that sometimes the snow squalls are short, maybe ten to fifteen minutes, and sometimes they last for an hour or more. I asked him for his suggestion on what to do.

In a suddenly steady tone of voice, as if he was quoting regulations out of the book, he said "Iím not going to suggest anything. You are the pilot, and you alone make the decisions regarding your aircraft and its safety. But, you might want to think about returning to your point of departure."

I thought about this for a minute, and then told him that I was still in good VFR conditions, and had over 3 hours of fuel in my tanks. I would proceed towards Halifax, and if necessary, wait nearby until the squall passed. If I began to feel uncomfortable with the conditions or the fuel, I would find an alternate (but probably not all the way back to Fredricton). He "checked my remarks", but did not encourage or discourage my decision.

At 10 miles out, he said that he couldnít see the ends of the runway. I told him that I could see some snow to the west and south (where the airport was), but where I was, and continuing to the east was perfect VFR below the clouds. He decided to let me use runway 15 for the straight in approach, to minimize the amount of time spent in the circuit and in the possible snow squall.

At 5 miles out, he still couldnít see more than a mile, but I could see the runway clear as anything! By now, runway 15 was no longer available though. (I found out later that Halifax controllers use all runways if the wind is below 10 knots, since it shifts anyways. They try and make it convenient for the pilots.) A larger, faster aircraft was coming in on runway 33, so he asked me if I could take the right-hand downwind for runway 33.

When I entered the downwind, the controller called in an excited, and obviously relieved voice. "The snow squall just ended, and I can see you in the right-hand downwind for 33 (which is also the right base for 24). Would you like to turn and use 24 instead?" I could hear in his voice that he wanted me down as soon as possible. I agreed, and landed without incident. It occurred to me that he had just experienced a rougher landing than I had. At no time was I in less than VFR conditions, but he was for quite some time. I thanked him generously for his assistance, and his patience.

Then, I had to smile. I had completed the journey in three days. Safe and sound. And happy.

Day Four (Saturday) ... The Return Trip

After reaching my hotel room the night before, I called my family in Toronto to close my "other" flight plan. Then I started calling the airlines trying to find a flight back to Toronto. I found a Canada 3000 flight at 1045 local, but was told to be at the airport for 0845 local to purchase the ticket. Needless to say, I arrived in plenty of time.

So, what can a pilot to do for 2 hours in a strange airport? Visit the control tower, of course!

(But you already knew that, didnít you?)

When I got to the tower, I introduced myself as the pilot that flew in during the snow squall on the previous night. One of the guys had been working then, but was on a break, so he had first-hand knowledge. The other guy had heard about it from the other controllers. By the time I left the tower, two other controllers has showed up for their shifts, and both of them had been working the night before, including the controller that had worked himself into a sweat bringing me down. I shook his hand and thanked him again for helping me. Then, I left for the flight home.

I visited the flight deck of the A320 on the way home, but I was only in there for a very short time.

Epilogue

In a nutshell, I covered almost 3500 miles in 4 different airplanes (B737, DH8, PA28, A320), logged over 20 hours cross-country hours in my log book, visited 9 airports (six for the first time), got the stamps to prove it, learned a lot about Canadian geography, actually used a DRCO, and visited two control towers.

Oh yeah, and I had some fun too!